I came across the term “Aridoamerica” in readings on the archeology of Southwestern North America. It struck me as brilliantly useful term for describing the cultural and ecological distinctiveness of the zone I call home.

Aridoamerica makes an excellent study in the layered complexities of human ecology. To understand the the ethnobiology of a place and its context in the world, it is helpful to examine the interplay of culture, evolution, and geography at various time scales.

One of the more fascinating aspects of North American linguistics is the geographic span of the the Uto-Aztecan language family. Linguists theorize that the predominate native languages of the Great Basin Desert are related to the the language of the Aztecs. Peoples that share an ancestral language tend to share other kinds of culture. Related Uto-Aztecan cultures occupy the greater part of arid Western North America and may be especially well adapted to the Aridoamerican environment.

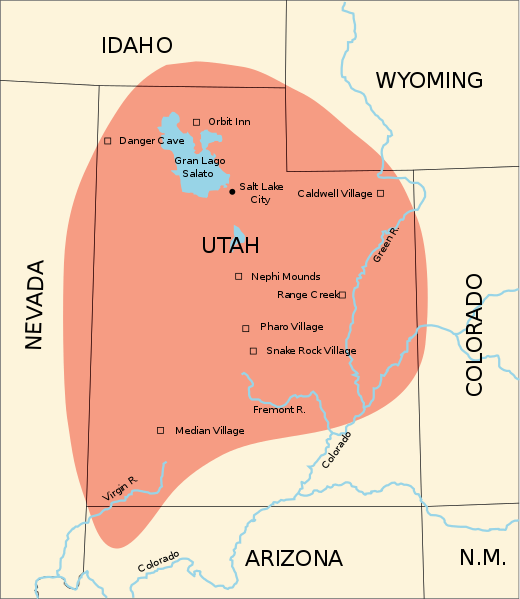

Archeologists have drawn the boundaries of Aridoamerica in various of ways. They generally place Aridoamerica’s Northern boundary well to the south of where I live (the Columbia River watershed, in the territory of Interior Salish and Sahaptin speaking peoples). In a strict cultural sense, one might draw the Northern boundary of Aridoamerica at the Northern extent of the prehistoric “Fremont culture”. These people were maize farmers, who probably spoke Uto-Aztecan and ranged into Northern Utah and perhaps had contact with my Columbia River watershed. This definition of Aridoamerica incorporates linguistic continuity and the continuity of particular cultural adaptations like the flexibility to forage or farm maize.

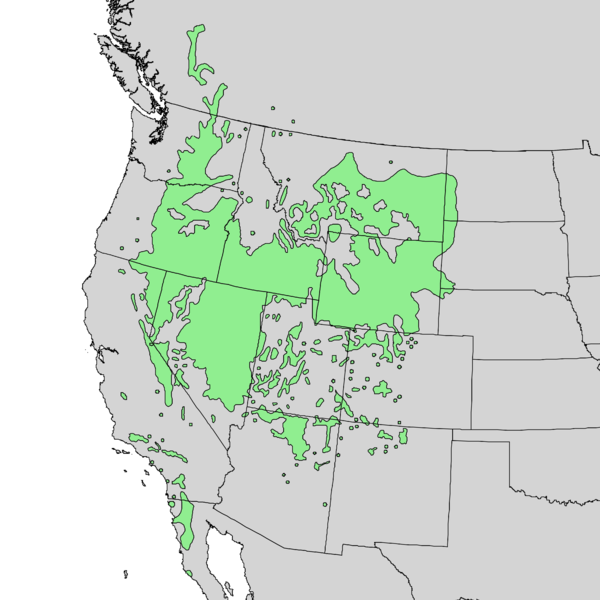

I borrow the concept of Aridoamerica for broader applications. Ecologically, it might make sense to extend the Northern boundary of Aridoamerica across similar biomes, to include the whole range of keystone species like big sagebrush or ponderosa pine. These and related species characterize the greater bioregion.

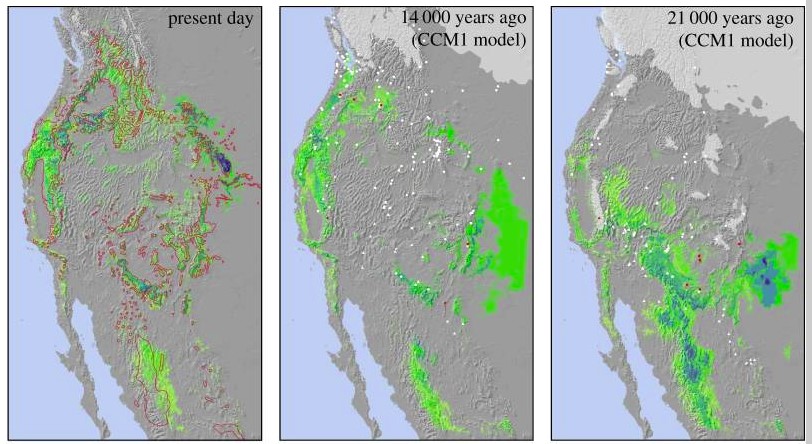

below: Artemisia tridentata natural range

In my ecological conception, the northern limit of Aridoamerica extends to include the entire range of the ponderosa pine. The Columbia River is a very distinct cultural area, if only due to a richness of fish and fishing culture. But terrestrial resources are similar across this zone, and there are some cultural similarities despite language boundaries. This zone is similar to what has been called the Intermountain West (plus the Baja Peninsula and the drier parts of California). I’m fond of referring to this zone as “Great Nation Intermontaña” (as distinct from The Evil Empire of Cascadia).

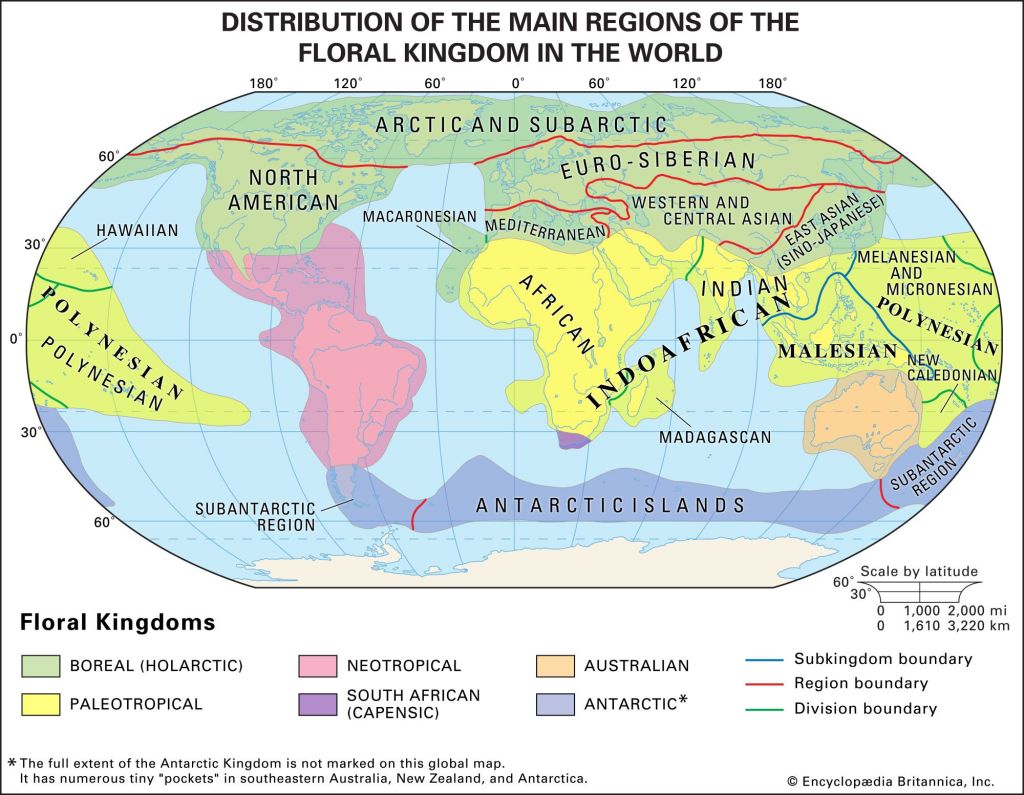

My own conception of Aridoamerica also considers a region of distinct plant life once called the Madrean Floristic Province. The plant life that makes Aridoamerica most unique in the world evolved in the Madrean Region.

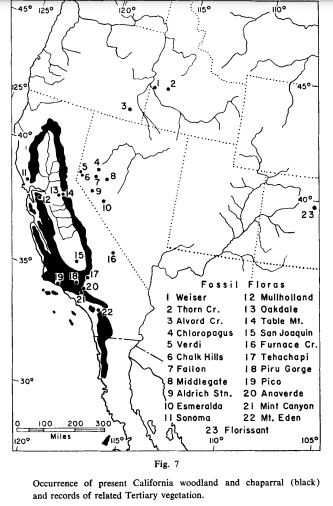

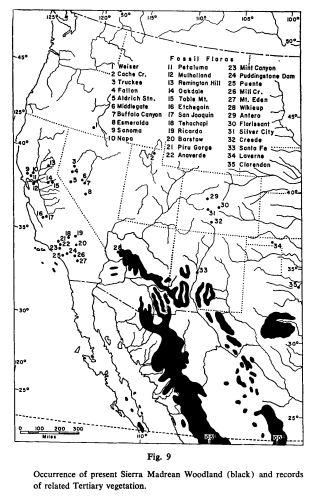

A floristic province is a useful concept because it accounts for both the evolutionary origins and the current distributions of plants. This is particularly important in Western North America, where radical climate changes and migrations have occurred in the wake of ice ages.

The story of the ponderosa pine mirrors the story of the broader Madrean flora. The ponderosa pine likely evolved in the vicinity of the Sierra Madre Mountains in Northwestern Mexico. The Madrean Floristic Province takes its name from these mountains. The Sierra Madres have been a refuge for many plant species during the coldest parts of the ice age. Many of the places ponderosa pines grow today where covered in glacial ice during the harshest parts of the Pleistocene. At the end of the last Ice Age, the beginning of the Holocene Epoch, the climate became warmer and more stable. Ponderosa pines and many other species spread north from southern refugia like the Sierra Madres, colonizing the broader American West, as far north as Canada.

To be clear, the Sierra Madres weren’t the only refugia within what is called the Madrean Floristic Province. There were other refugia, like the Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains, which have been continuously forested since the age of the dinosaurs. And these refugia where not the source of ALL the plants that grow here today. Many of the plants growing within the Madrean Floristic Province are from taxa common across the Northern Hemisphere. Some of the region’s plants are ancient migrants from East Asia and other faraway places.

But the plants which make our region distinct in the world have a deep history here in the Madrean region. These plants have been migrating in and out of regional refugia for millions of years, in concert with climate fluctuations, often along predictable routes. Since the end of the last ice ige, Madrean plants have migrated mostly northward and upslope. As planetary warming accelerates in the present age, we might look south, downslope, and toward regional refugia for adapted Aridoamerican plant allies. These taxa have adapted to climate changes before. Human assisted plant migration may be sound conservation practice in some cases.

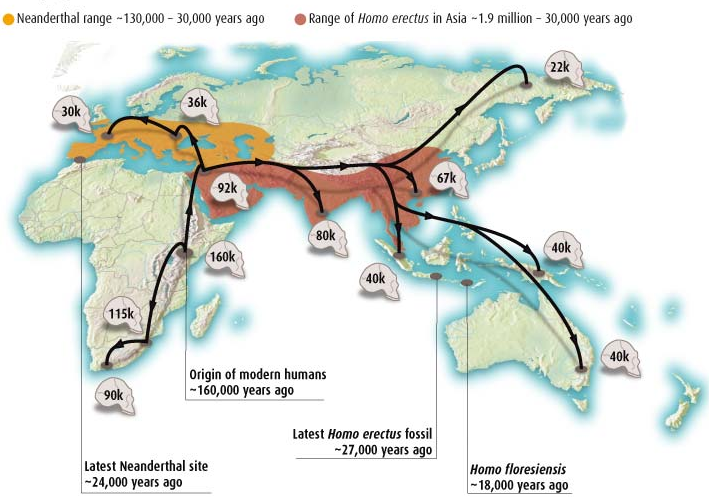

There is yet another layer involved in my conception of Aridoamerica- a comparison with the environments of human evolution. Our species emerged in the Eastern hemisphere, but the first humans to occupy Aridoamerica were able to thrive here partly because of evolutionary experience with similar environments in Africa and Eurasia.

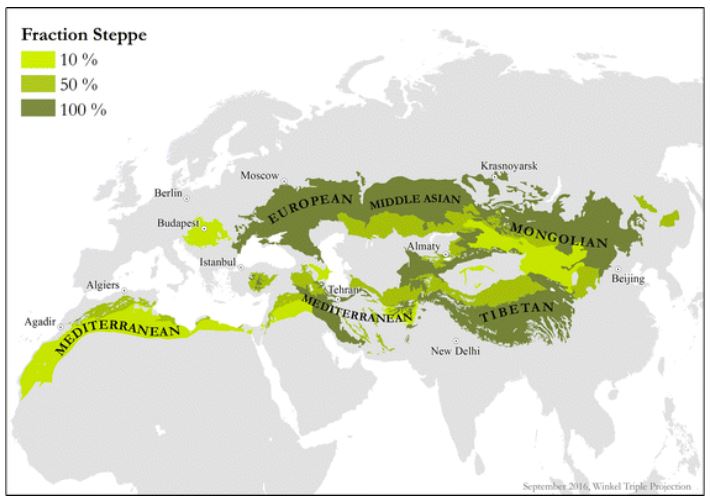

The flora Madrean floristic province has interesting commonalities with the Irano-Turanian and Mediterranean floristic provinces. These regions demarkate a band of plant life stretching from North Africa and Spain to the Himalayan foothills. The Madrean and the Irano-Turanian are both arid middle-latitude regions between the tropics and the cold boreal realm.

Human evolution connects with many world ecologies, but the first migrations of our genus out of tropical Africa followed a belt of arid habitat, which some paleoanthropologist have dubbed “Savannastan”. Savannastan was occupied much earlier than Western Europe and the wetter parts of temperate Eurasia. Aridoamerica is North America’s “Savannastan”.

It may by no coincidence that North America’s most technologically elegant nomad cultures share language and territory with the continent’s the most urbanized indigenous empire. Evolutionary amenability of a landscape lends itself to both atavistic lifestyles and rapid innovation. A similar pattern is seen in Eurasia, where the places most amenable to basic toolkits and early migrations became cradles of urban civilization.

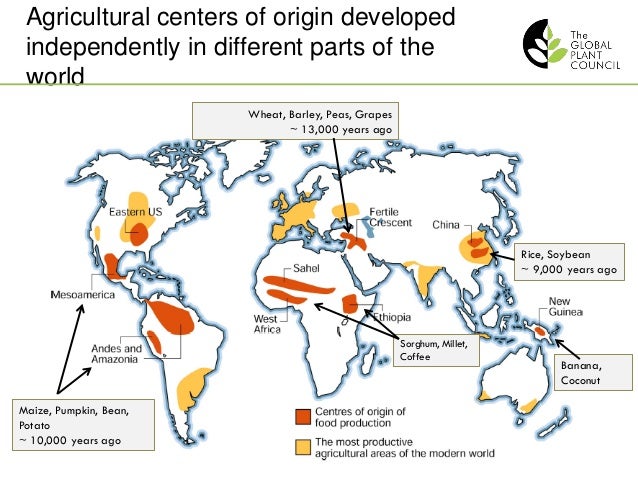

Temperate grasslands are similar to the tropical grasslands of our evolution, sharing many edible taxa. But cold-dormancy causes temperate grasslands to store more carbon in the soil, which makes them more agriculturally productive. Based on this alone, we would expect urban civilization to emerge somewhere like the East African cradle of our evolution but slightly cooler. The early development of agriculture around Mesopotamia fits with this theory. The range of important edible taxa like Ficus and Celtis illustrate elements of continuity between the Fertile Crescent and the environment of our Miocene/Pliocene/Pleistocene evolution. Ficus and Celtis are also present in Aridoamerica.

As in in Eurasia, North American agriculture was developed in semiarid regions at middle latitudes, eventually spreading north and south to more humid regions. Ironically, agricultural civilizations are more resilient in humid places. Many of the earliest agricultural lands have been desertified and abandoned. The centers of empire have shifted from fragile grasslands to resilient forested regions since early antiquity.

Where agriculture has originated independently in the tropics (in places such as the Sahel and SW Amazonia) it’s latitudinal and longitudinal spread has been ecologically constrained. Middle-latitude grasslands are distinctly fertile, extensive, and ecologically analogous, in a way that made the ancient commercial empires of Eurasian and North African possible. Only since the colonial era has commerce moved tropical crops extensively around the world.

From the perspective of the world’s most liveable places, the human trajectory is non-linear. As early as the Bronze Age, steppe environments were the stronghold of pastoral cultures which could be called “post-civilized”, at home in the aftermath settled agriculture and urbanity. Pastoral nomadism was competitive with agrarian civilization up until the Industrial Revolution. Great Basin hunter/gatherers played a similar role in Aridoamerican prehistory.

The arid Irano-Turanian had a disproportionate role to play in the the development of agriculture. The region hosts some of the world’s earliest examples of agriculture and spawned many of the world’s most important crops. A band of fertile grassland facilitated the ancient exchange of crops between independent centers of agricultural development in the Fertile Crescent and the Yellow River of China.

The Madrean is North America’s counterpart to the Irano-Turianian in this respect as well. Both regions were the epicenters and powerhouses of agriculture on their respective continents.

The success of agriculture and civilization in these regions, owes much to crops sourced from local biodiversity. Wild crop relatives and ancestors continue to play an important role in crop breeding. The richness of the Aridoamerican land gave to rich cultures.

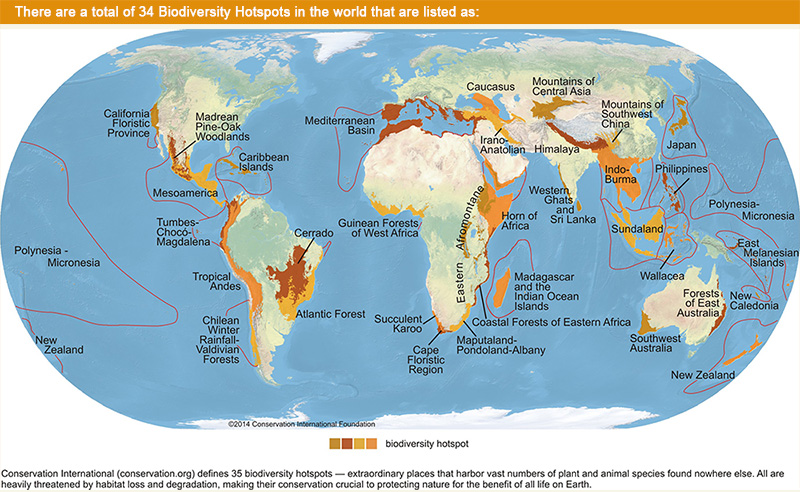

The California and the Sierra Madre Occidental are world biodiversity hotspots, hosting high numbers of species found only in these regions. These biodiversity hotspots correspond roughly to the dynamic glacial refugia described earlier. Over evolutionary time, these regions have functioned as both store and source for the evolutionary potential in the greater Aridoamerican region. These regions are to our biogeography what motherlands and capitol cities are to our cultures. Our fate as place-based beings is tied to the fate of our evolving biological community. All citizens of Aridoamerica would do well to invest in the integrity of our biodiversity hotspots. We owe them our allegiance.

Crops are only the most obvious gifts of biodiversity. The living environment provides us with more than food, energy, and materials- it also forms the basis of our commerce, technology, and culture. The ability of our ecological communities to adapt is the basis of our own ability to adapt in all of these arenas. Perhaps nowhere is the more apparent than on the arid rangeland the characterizes so much of Aridoamerica. The integrity of the range is the integrity of our wildlife, our livestock, and our distinctive ways of life. Every tiny songbird and wildflower contributes something that integrity. We are better hunters, herders, travelers, storytellers, and leaders for the richness of this land.

In spite of industrialization, biological richness remains indispensable in the struggles than define humanity. The living elements or our environment underwrite our social currency- our cultural distinctiveness, sophistication, creativity, and wisdom. Even in the depths of our culturally constructed worlds, plants and animals inform our adaptations in the realms of emotion, mythology, and art. Biodiversity is crucial to the vitality of individuals and societies on tumultuous planet.

I’ve drawn the crudest outlines here of the human relationship with Aridoamerica. I’ve begun to map Aridoamerica as a biocultural unit by laying down a series of overlapping descriptive layers for comparison. Some of my layers apply to different moments in time. Moving through the temporal layers effectively animates the map like a flip-book.

To understand the scope of cultural complexity in ethnobiology, one must begin with an examination of contemporary and historic cultures. We can broaden our understanding by making comparisons of culture across biogeography and short spans of time. But this is a snapshot view of relatively static phenomena. Cultural adaptions develop over thousands of years. Understanding bioculture as an adaptive process requires an archeological perspective. Yet, from this perspective, we still cannot fully define the study of bioculture. Over mere thousands of years, biological adaptation is not discernable and its relationship to cultural adaptation cannot be understood. To define bioculture we must take an evolutionary perspective, and think in terms of millions of years.

ARIDOAMERICAN ASSOCIATES (to be continued…)

ACACIELLA (PRAIRIE ACACIA)

ACMISPON (DEER VETCH)

AGASTACHE (HORSEMINT)

AGAVE

AGOSERIS

ALLIUM*

AMARANTHUS

ABROSIA (BURSAGE/RAGWEED)

ARBUTUS (MADRONE)

In the Sierra Madre Occidental: Arbutus bicolor and A. madrensis in temperate and cold climates, A. arizonica in semi-dry temperate climates, A. tessellata in warm-temperate climates, and A. xalapensis in humid temperate climates, as well as the dwarf strawberry tree A. occidentalis. in semi-cold forests. COMAROSTAPHYLIS

ARCTOSTAPHYLOS (MANZANITA)

ARGEMONE (PRICKLY POPPY)

ARTEMESISA (SAGEBRUSH)

ASCLEPIAS (MILKWEED)

ASTRAGALUS*

ATRIPLEX

BOECHERA

BRODIAEA (WILD HYACINTHS)

BALSAMHORIZA (BALSAMROOT)

CALLIANDRA (FAIRY DUSTERS)

CALOCHORTUS (SEGO LILY)

CAMASSIA (CAMAS)

CASTILLEJA (INDIAN PAINTBRUSH)

CEANOTHUS (MOUNTAIN LILAC)

CERCOCARPUS (MOUNTAIN MOHAGANY)

CLARKIA

CHAENACTIS (DUSTY MAIDENS)

CHENOPODIUM

CHLOROGALLUM (AMOLE LILY)

CHRYSOLEPIS (CHINQUAPIN)

COLEOGYNE (BLACKBRUSH)

COLLINSIA (BLUE EYED MARY)

CURCUBITA

DALEA (PRAIRIE CLOVER)

DASYLIRION (BEARGRASS)

DELPHINIUM (LARKSPUR)

DESMANTHUS (DONKEY BEAN)

DODECATHEON (SHOOTING STAR)*

ECHINOCEREAUS (HEDGEHOG CACTUS)

EPILOBIUM

ERICAMERIA (RABBITBRUSH)

ERIGERON (WILLOWHERB)

ERIOGONUM (DESERT BUCKWHEAT)

ERIOPHYLLUM (OREGON SUNSHINE)

ERYTHRANTHE (MONKEY FLOWER)

ESCHOLIZIA (POPPIES)

FALLUGIA (APACHE PLUME)

FRASERA

FREMONTODENDRON (FLANNEL BUSH)

GILIA

HELIANTHELLA

HESPEROCYPARIS (CYPRESS)

HESPEROCALLIS (DESERT LILY)

HETEROMELES (TOYON/HOLLYWOOD)

HOLODISCUS (OCEANSPRAY)

HOITA

HOSACKIA (DEER VETCH)

HYDROPHYLLUM (WATERLEAF)

IPOMOPSIS (SKYROCKET)

LEPIDIUM

LEUCEANA (HUISACHE)

LEUCOCRINUM (MOUNTAIN LILY)

LEWISA (BITTERROOT)

LITHOSPERMUM (PUCOON)

LOMATIUM/PANA CLADE (BISCUITROOT)

LUPINUS*

MADIA (TARWEED)

MENTZELIA (BLAZING STAR)

MONARDELLA (COYOTE MINT)

MIMOSA (TEPEZCOHUITE)

MIRABILIS (FOUR O’CLOCK)

NOTHOLITHOCARPUS (TANOAK)

OEMLARIA (INDIAN PLUM)

OENOTHERA (EVENING PRIMROSE)

OPUNTIA (PRICKLY PEAR)

PEDIOMELUM (BREADROOT)

PENSTEMON

PERAPHYLLUM

PHACELLIA (SCORPIONWEED)*

PHASEOLUS (BEANS)

PHLOX (diversity hotspot is Baker Co., OR)

PHILADELPHUS (MOCK ORANGE)

PINUS (NUT PINES)

PROSOPIS (MESQUITE)*

PSORALIDIUM (SCURF PEA)

PSOROTHAMNUS (SMOKE TREE)

PURSHIA (CLIFFROSE)

QUERCUS (OAKS)

Section Protobalanus

RIBES (GOOSEBERRY)

RUPERTIA

SALVIA (CHIA)

SENECIO

SEQUOIADENDRON (SEQUOIA)

SIDALCEA (CHECKER MALLOW)

SILENE (CATCHFLY)

SOLANUM (PEPPERS, POTATOS, TOMATOES)

THERMOPSIS (GOLDEN BANNERS)*

TOXICOSCORDION (DEATH CAMAS)

TRIFOLIUM (CLOVER)*

TRITELEIA (WILD HYACINTH)

UMBELULARIA (BAY LAUREL)

WYETHIA (MULE’S EARS)

YUCCA

ZEA (MAIZE)

GENERAL ARIDOAMERICA

Flora of the Western US

Plant Families of the Arid Western US 1

Plant Families of the Arid Western US 2

GUIDES TO TAXA

Conifers of Western North America

A Guide to Common Locoweeds and Milkvetches of New Mexico

SPECIALIST INSTITUTIONS

North American Rock Garden Society Seed List

Cactus and Succulent Society of America

Desert Legume Program

American Conifer Society

Conifer Country, Conifers and Manzanitas of the Klamath

NURSERIES AND SEED SUPPLIERS

Nobody Nursery

REGIONAL FLORAS

Vegetation of the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico: a synthesis

Native Pollinator Plants for Southern Oregon

Wildflowers of Arizona

Plants of the Gila Wilderness

Southwestern Trees

Trees of the Gila Forest Region

New Mexico Range Plants

New Mexico Plant Guides

The Distribution of Forest Trees in California

Biotic Communities of the Southwest

Potential Natural Vegetation Types of the Southwest

USGS Plant Communities

Biotic Communities of the American Southwest (big download)

Yavapai Native and Naturalized Plants